|

Profiles in Patriotism

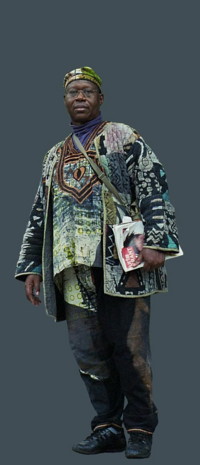

James Credle

Some Kind of Hero

by Denny Meyer

|

|

James Credle took a bullet a long ago in a jungle in Vietnam. He fell to the ground, got up, and continued to help evacuate other injured soldiers. He was a medic. "It was in Tay Ninh Province, down below Saigon near the rubber plantations. We were doing a lot of S & D (search and destroy) missions," He told me. "We were going thru jungle trying to evac. a severely injured soldier; we were cutting our way thru jungle to get to the air evac. location; and bullets began to fly past us, we ducked down to ground, when it stopped we resumed. That happened three times. The fourth time, I was hit. I was patched up and we continued onward. Later, of course, I had to join him on the med evac. helicopter."

It doesn't sound like much, does it? Unless, of course, you're on a rescue mission in a jungle thousands of miles from home surrounded by Viet Cong guerrillas trying to kill you.

James Credle was drafted into the US Army and served from 1965 to 1967, leaving as a Spec. 4 Medic. He received a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star with V for Valor, the Vietnamese Cross for Gallantry, and an Army Commendation Medal among other awards for his service. He happens to be a gay American and a black American. Neither of those has anything to do with being a hero nor with being qualified and able to serve in our nation's armed forces. In 1948 President Truman integrated black Americans into our armed forces by executive order, prohibiting racial discrimination in our military and recognizing the courage and valor of black Americans who have served in World War II and since. And yet, this brave proud American soldier could have been dishonorably discharged due to the discriminatory policy against gay Americans serving in our armed forces, despite his heroism in combat in Vietnam. Today, under the Don't Ask Don't Tell policy, those serving in Iraq and Afghanistan still must hide who they are if they are gay. Gay American service members are still discharged today, at the rate of two per day, despite heroism and critical skills, simply because of a policy that selects them for discrimination. And every year, some 3500 gay American service members simply do not reenlist because of the unbearable burden of serving in silence; a full brigade of trained, skilled soldiers lost each year.

When he was drafted, James Credle knew that he was gay, but said nothing--in essence volunteering when he could have avoided serving. "I didn't think about not serving," he said. "I was working at a Veterans hospital in Lyons, New Jersey, helping mostly WWI, WWII, Korean War, and newly hospitalized Vietnam vets; I heard all their stories, I knew what to expect. I knew about the reality of being in a war. I went, it was the right thing to do." He was 20 years old at the time.

|

In Vietnam, as it is today in Iraq, he was able to be open with those around him. When mortars and bullets are flying, no one cares if the man next to him happens to of a different race or sexual orientation or both. At times like that, he said, "we anticipate that we might not come back, we're open with each other, it might be the last chance we have to relate honestly with another human being."

And yet, while serving in Vietnam as a young man of 20, he began to understand the meaning of discrimination against others. "While I was in Vietnam, in 1967, I saw the area where I lived in Newark burning during the 1967 Newark riots-"rebellion." I was fighting for my country and saw my home burning due to police brutality. I began to more deeply understand how it feels to be treated as less than human. And often, in war, we kill others when we consider them to be less than human; on both sides. I call on those who understand racism to realize how they condemn their own children and others for being gay. How dare they claim that as the right path?"

James Credle grew up in the south, in North Carolina, where he saw "White Only" water fountains and toilets, where he had to sit outside eating his lunch from a paper bag, where he was bussed past white Pamlico County "High" school to what was the black Pamlico County "Training" School. "In the military, as a gay person, all of that impacted on my experience. I came to better understand the world."

|

Sadly, he saw racial conflict within our own armed forces while he was serving. "Many vets of color were dishonorably discharged. Even now, forty years later, some are homeless or in prison." He explained that many were unable to overcome double discrimination when they tried to transition back to civilian life. Vietnam vets were not welcomed home as heroes and black vets returned home to the same employment discrimination they faced before having served their nation. "At that time," Mr. Credle said, "people used the bible to condone racism; now they use it to condone heterosexism. Both use power to put people on a lower level than themselves. It has been empowerment by race and now its discriminatory empowerment by sexuality." He believes that it is important to challenge people to think about their bigotry, "in order to create a different world, not recreating the mess we came from."

After his service in Vietnam, he went back to work at the VA hospital, and studied sociology at Rutgers University, under the GI bill, graduating third in his class. He became a counselor for veterans, working at Rutgers for 37 years becoming Director of the Office of Veterans Affairs, and later, the Assistant Dean of Students.

|

Over the nearly four decades following his experience in Vietnam, he was a founding member of the National Association for Black Veterans, a founding member of New Jersey & National Veteran Programs Administrators, Vice Chair of the New Jersey Agent Orange Commission, and the Executive Director of the National Council of Churches' Veterans in Prisons program (serving 23 programs around the US, developing programs to assist veterans in prison; and developing a 'discharge upgrade project'). He was also a founding member and co-chair of the National Association of Black and White Men Together, and its New York affiliate Men of All Colors Together/New York.

Currently, he is a founding member of the Newark Pride Alliance, following the murder of Sakia Gunn, which is seeking to create a community center and safe spaces in Newark for LGBT people; and strives to build community understanding to alleviate abusive bias and discrimination against the LGBTIQ and Two-Spirited community.

|

"In my upbringing there was no place for anger," he said, "that's a luxury. My parents had 14 children, in our home there was no place for anger; it was more about trying to live another day. As in Vietnam, when the bullets were flying, there was no time for protest. We were busy trying to save lives. If you're still alive, later, then you can protest."

Guided by his rearing and his realization, during combat in Vietnam, that conflict was dehumanizing, he devoted his efforts for nearly 40 years to creating change for the better. He's some kind of hero.

© 2007 Gay Military Signal

|